Upon entering Malta, there were two aspects that caught our attention. Firstly the amount of building work and the style of building which gives the urban landscape its unique look, and secondly the multiple similarities to the UK such as road signs, shop fronts and makes of car. As the fieldtrip progressed, this dichotomy increased. On one hand, the vegetation, climate and general atmosphere were definitely Mediterranean, whilst the nature of shopping centres and seaside towns had a distinctly familiar aspect to it. These observations, linked to the background information, led the group to decide to investigate just how much influence tourism has had on the development of a traditional fishing village.

Goffman (1959) provided a dualistic view that tourist, and local areas and culture are separate. From our first impressions, it seemed that this might be correct. Recent research has found this not always to be so and that rather there is a continuum, as proposed by MacCannell (1976). Pearce (1999) defines tourist environments as those with 'high transient populations, a number of physical modifications to facilitate the inspection of the locale, and an inherent structure to control visitor accessibility.' The aspect of control of accessibility lends weight to ideas of limits to tourist's geographies. It is also possible that these same limits will affect locals in a similar way. According to Erb, 'Tourists are consistently associated with the unpredictable and the unknown [due to] their greater ignorance of local cultural norms.' This is a concept well developed by feminist geographers such as Rose (1993), Pain (2000), Valentine (1998) and Smith (1987). In the case of Malta, their acceptance of most things British and thus the reduction of the 'unknown' may well reduce the relevance of this theory. As a consequence however, the theory may well apply more to tourists of nationalities other than British. Although the locals are dominated by the tourists, Evans-Pritchard (1989) proposed that often they can 'control what they absorb into their own culture and can use parody and ridicule to provide control.'

Due to the nature of our research we intentionally kept our aims as simple

and as realistic as possible. Therefore, we aimed to:

1. Investigate Goffman's (2001) assertion that tourism and local culture are

clearly spatially defined .

2. Ascertain how many 'physical modifications' have been made to the structure

of the village in order to accommodate tourism and what affect this has had

on the village.

3. Ascertain how much the locals have 'absorbed into their own culture'.

The location for the study was chosen to be the town of Bugibba. This location

was based primarily on information given to us by John Stainfield through his

vast experience of the Maltese islands. Upon examining the location and discussing

the area with the aforementioned, it was decided that the study would include

from the area known as San Pawl il-Bahar (St. Paul's Bay) and Qaura as well

as Bugibba. This was because it is all one urban area and also that the area

of San Pawl was said to be the 'old part' of Bugibba.

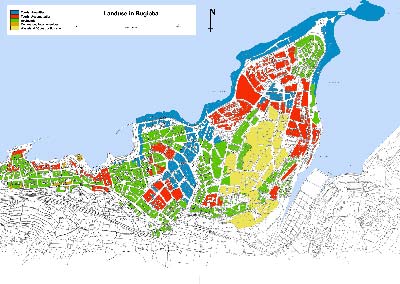

In order to achieve the first aim it was proposed that we undertake a classification

of building usage throughout the town of Bugibba. This was initially proposed

to be undertaken upon an individual building level, however considering time

and resource restrictions it was decided that each street's usage would be generalised,

with a more detailed description noted down to provide the more comprehensive

information that is lost through generalisation. We proposed four categories

before the research. Tourist amenities and Tourist accommodation represent the

tourist influence on the town, while Residential and Local amenities represent

the local population. The fifth category was added during the fieldwork when

areas within the town were unexpectedly found to be undeveloped. Problems encountered

with the data collection were mostly encountered when trying to generalise a

street with many disparate uses on it. For example, many streets especially

in the San Pawl area contained both local amenities, tourist shops and residential.

The largest problem encountered however, was differentiating between residential

and tourist accommodation. With hotels it was easy to designate tourist, however

when trying to ascertain whether an apartment was tourist or residential, there

was not much hope. Often, clues such as the type of name on the doorbell, or

cars parked outside were used to aid a guess at the building use, however this

obviously was unreliable. As a Maltese estate agent told us, the only way to

know for sure was to knock on the doors, or follow the policemen round whilst

they deliver the postal votes for the elections. Consequently, the data produced

for this is very general and highly inaccurate.

In order to have more information to attempt to distinguish a local from a tourist

area if such were to exist, a street quality index was created that would provide

a score for each street based on five indicators. Litter was chosen, as a presence

of litter would indicate that the area was neglected. Graffiti was chosen for

similar reasons, although this would also indicate a social unrest. The building

quality in each street would again indicate the attention an area received and

perhaps the wealth of the owners. Traffic congestion and parking were chosen

to indicate attractiveness of an area. These were all rated on a scale of 1

to 5, with 0 indicating no presence. The scores were then summed and adjusted

in order to provide a total score out of 100.

Relating to both the first and the second aim, the age of buildings was also

recorded. Similarly to before, it was intended for each building to have an

age associated, however an average age for each street was provided with any

outstanding features detailed in the extra notes for each street. The age of

buildings can help in designating tourist from local if Goffman's (2001) assertion

that 'old' areas dominated by residents and 'new' areas by tourists is correct.

A correlation between residential and old areas would indicate this. Great difficulty

was found in trying to acquire this data. Not only did the age vary along the

street, but it also varied vertically. There was a tendency for new storeys

to be built on top of existing housing (as shown in Figure 1).

Therefore it was very difficult to classify the age of a street as it could

fall into all categories.

Figure 1 - A house in Bugibba with three storeys,

all built at different times.

In addition to the Quantative data produced, in order to explore more fully

the social relationships of tourists and locals and to tap a potential resource,

namely the memories of repeat visitors, it was felt necessary to undertake a

number of short, unstructured interviews which would provide 'rich sources of

data on people's experiences, opinions, aspirations and feelings' These interviews

would then be transcribed and analysed, generalising opinions and linking ideas.

From this we hoped to glean information about the town's physical development,

and opinions about the tourism industry. Interviews with tourists would give

their impressions of the locals, and vice versa.

Additionally, an interview was conducted with Mr Scalpello of the Malta Planning

Authority. From this meeting we acquired a number of secondary sources including

aerial photographs, maps of their land-use survey and details of their planning

policy.

When analysing the Quantative data it was first apparent that there wase indeed evidence of zonation. Figure 2 shows that land-use is clearly defined, with tourist features dominating the sea front and most residential being further inland. There are pockets of residential amongst the tourist, but mostly the residential is in clearly defined areas. Figure 3 shows that there are clear areas of differing quality. The worst area corresponds very well to that area of wasteland and construction. This was expected. The best quality areas are shown to be along the sea front and also along the centre of the village moving inland. The worst area is clearly defined in San Pawl. There is some correlation between the two maps, with areas such as the 50-59% area in San Pawl corresponding exactly with a residential area. A block of tourist residential in San Pawl corresponds exactly with an area of >70% and similarly and area of tourist residential on the coast near Qawra corresponds exactly with an area of >70%. Figure 4 also shows clear areas within the town. This shows that the oldest buildings, from 1968 are along the sea front with a section of buildings from 1988 in the centre of the town. The newest buildings occur in a cluster around the waste ground. This map doesn't correspond to either Figure 2 or Figure 3. The newest building does however correlate with an area of residential. It is fair to say that the data for this map was so unreliable that it should actually be discarded.

The qualitative data produced a number of results. Overall, the Maltese and

British got on famously. There was an acknowledgement of the long shared history

and so there is a shared interest in each other. There is also a lot of intermarriage

that has very blatant influences on culture. For example, an estate agent who

was married to an English woman was noticeably using cockneyisms in his speech

although for the most part his accent was Maltese. The interviews both confirmed

and rejected the assumption of Goffman (2001) in that the general impression

was of social integration but physical segregation. One Maltese gentleman said

that the San Pawl end was Maltese and that 'the Maltese get together and chat

in the evenings, and we won't find that many British'. However, the estate agent

told us that residential and tourist accommodation was all mixed in together

throughout the town.

A number of people told us about the renovations the town has undergone in the

last ten years, with the addition of a plaza in the centre around which cafes,

restaurant and shops cluster. This acts as a focal point for tourists. One couple

said that 'its one of those places where your not at any risk and they seem

to welcome you in their own little local bars as much as the hotels.' This implies

an acceptance of British culture into the native daily routine. Another example

is what's on offer in the cafes and restaurants. A Scottish lady said 'People

come and they just want burgers and chips' and consequently that is provided

for in almost every café and restaurant. One observation was that although

the area was once a fishing area, the only sign of fishing left were the traditionally

highly painted boats in the harbour and even these were too small to be of any

commercial use today. A Maltese gentleman told us 'although there are some fishermen,

mostly tourists and people who just come fishing to pass the time, not to live

on.' He told us that the majority of fishermen now operated tour boats. This

shift in industry has dramatically altered the lifestyles of those involved.

For example, according to the estate agent interviewed, they have to allow for

the seasonality of the business, 'they have to make their living in them six

months, seven months.' Also, in the last ten years more and more businesses

have become involved so that now 'There are more dogs to share the bone' and

even though tourist rates have increased, the income per business has stayed

level.

The major thrust of the planning policy for the area is development in order

to make it more suitable for tourism. There are measures to encourage entertainment

facilities in certain areas (See Table 2 and Figure

5, NWSP16) and to retain residential areas as such (See Table

2 and Figure 5, NWSP19).

The data collected has proven to be insufficient to provide any conclusive results. However, it is possible to conclude that there is an element of spatial separation of tourist and local both physically and socially. The planning department is clearly reinforcing this division. At the moment there is an easy relationship between local and tourist, however if this pattern continues there are a number of questions that will need to be addressed. Primarily, will the idealised relationship continue if local and tourist are segregated; is it necessary to have spatial integration for social integration? Or, would the continued overlapping of functions have lead to a disturbance of the tranquil relationship anyway? It is clear however that the village has been obviously modified in order to make it more accessible to tourists, most notably in the plaza and seafront, but also with the bypass reducing the volume of traffic flow through the town. The area has lost most traces of the traditionally industry of fishing in order to accommodate tourism and thus Peace's assertion has been proven correct in this situation. There is however slight doubt as to how much foreign culture has been absorbed into the Maltese culture. On a surface level, the cafés and shops display a significant adoption of British customs. However, 'after hours' they seem to revert to the more traditional Maltese ways, sitting and talking, swimming and fishing. It seems that Evans-Pritchard's assumption that locals can 'control what they absorb into their own culture' can be confirmed in this situation.

Chang, T. C., (2000) 'Singapore's little India: A tourist attraction as a contested

landscape' Urban Studies 2000, 37(2): 343-366

Del Casion, V.J., Hanna, S.P. (2000) 'Representations and identities in tourism

map spaces' Progress in Human Geography 24(1): 23-46

Ellul, T., 'General background to tourism development and planning concerns'

Environmental Themes in the Mediterranean: A Case Study of the Maltese Islands

website: http://www.geog.plymouth.ac.uk/malta/Malta.htm, last accessed 14 September

2001

Erb, M., (2000) 'Understanding tourists - Interpretations from Indonesia' Annals

of Tourism Research, 27(3): 709-736

Evans-Pritchard, D. (1989) 'How "They" see "Us": Native

Americans Images of Tourists' Annals of Tourism Research, 16: 89-105

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday life, Doubleday, Garden

City, NY

Hasanean HM, (2001) 'Fluctuations of surface air temperature in the Eastern

Mediterranean', Theoretical and Applied Climatology 68(1-2): 75-87

Hubbard, P., Lilley, K. (2000) 'Selling the past: Heritage-tourism and place

identity in Stratford-upon-Avon' Geography 85: 221-232

Johnson, N.C. (1999) 'Framing the past: time, space and the politics of heritage

tourism in Ireland' Political Geography 18(2): 187-207

MacCannell (1976) The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class, Schocken Books,

New York

Mayes J (2001) 'Rainfall variability in Maltese Islands: Changes, causes and

consequences' Geography 86: 121-130

Pain, R. (2000) 'Place, social relations and the fear of crime: a review', Progress

in Human Geography, 24(3): 365-387

Pearce, D. G., (1999) 'Tourism in Paris - Studies at the microscale' Annals

of Tourism Research, 26(1): 77-97

Preston-Whyte, R. (2001) 'Constructed leisure space - the seaside at Durban'

Annals of tourism research, 28(3): 581-596

Ricardi di Netro T (2000) 'The Knights of Malta and their territory. Liguria

between Lombardy and Provence during the 13th to 17th centuries. Paper from

the September 11-14,1997 Genoa conference' STUDI PIEMONTESI 29(2): 685-686

Rose, G. (1993) Feminism & Geography - the limits of Geographical knowledge,

Polity Press, Cambridge

Smith, S. (1987) 'Fear of Crime: beyond a geography of deviance', Progress in

Human Geography, 11(1): 1-23

Thornton, P.R., Williams, A.M., Shaw, G. (1997) 'Revisiting time-space diaries:

an exploratory case study of tourist behaviour in Cornwall, England', Environment

and Planning A, 29(10): 1847-1867

Valentine, G (1992) 'Images of danger: women's sources of information about

the spatial distribution of male violence.' Area, 24(4): 22 - 29

(http://www.science-plymouth.ac.uk/departments/geography/malta/geol.htm)

|

Formation

|

Approximate Age

|

Maximum Thickness (m)

|

|---|---|---|

| Upper Coralline Limestone | 12 -7.5 Ma | 104-175 |

| Greensand | 12 - 7.5 Ma | 0 - 16 |

| Blue Clay | 13 - 12 Ma | 0 - 75 |

| Upper Globigerina Limestone | 15 - 13 Ma | 5 - 20 |

| Middle Globigerina Limestone | 20 - 15 Ma | 0 - 110 |

| Lower Globigerina Limestone | 20 - 15 Ma | 5 - 110 |

| Lower Coralline Limestone | 140 (visible)236 (borehole) | |

| Clays and dolomitised limestone | + 3000 (borehole) |

Table 2 - Overview of some important planning policies.

|

NWSP 16

|

The entertainment priority area of Bugibba. All properties with frontage on the streets indicated on the map are to be considered as being within the entertainment priority area. Acceptable land uses in this area are: food/drink outlets, amusement arcades, pubs/clubs/bars (providing there is no excess disruption to neighbours), tourist accommodation and visitor attractions. |

|---|---|

|

NWSP 19

|

The St. Paul's Bay/Bugibba/Qawra residential areas. Acceptable land-uses in these areas are: dwelling units, residential institutions (providing there are no adverse impacts on the amenity of the area), retail outlets, offices, food and drink outlets, tourist accommodation facilities, visitor attractions, educational facilities. All these must comply with regulations etc which are not listed but might be on the website. The primary aim of the policy is to guide the future development of the residential areas by encouraging the location of more dwelling units within them. Land-uses outside dwellings must support and enhance the residential area and not create adverse environmental impacts. |

Figure 2 - Land use in St. Paul's Bay and Bugibba

Figure 3 - Street Quality in Bugibba

Figure 4 - Approximate ages of buildings in Bugibba

Figure 5 - North West Local Plan: Bugibba and Qawra Policy Map